Artist feature: Melanie Mowinski on "Women Walking to Water"

- Sm[ART] Commons

![Writer: Sm[ART] Commons](https://static.wixstatic.com/media/aeb1f8_e9baee42902040cfa974efe471b66c57%7Emv2.jpg/v1/fill/w_32,h_32,al_c,q_80,enc_avif,quality_auto/aeb1f8_e9baee42902040cfa974efe471b66c57%7Emv2.jpg)

- Mar 14, 2025

- 5 min read

Updated: Mar 21, 2025

In this interview with Melanie Mowinski, we dive into the transformative journey of an artist whose work is deeply inspired by nature. From the deserts of the American Southwest to the waters of Tennessee, her connection to the earth has shaped not just her artistry but also helped to start powerful dialogues around women, water, and community.

Enaya: How long have you been creating art inspired by nature?

Melanie: It all started after college when I lived in the American southwest and then went into the Peace Corps Volunteer on the island of Saint Kitts. I was raised in a very Catholic family, but “church” in the traditional sense didn’t work for me anymore. Instead, I discovered the holy power of that natural world. I explored these ideas while pursuing my first master's degree at Yale University–looking for the connections between nature, spirit, and art. Then, in 2005 I moved to Philly from the Berkshires and while I didn’t realize it at the time, I was surrounded by concrete, very little trees. It was at this point that my creative practice became centered in the natural world. By creating work about and with nature I was able to find myself again–I need to be in the woods, in water, in nature. The artwork was/is one of my ways of bringing the essence of the natural world to inside spaces but also my way honor the great spirit of the universe.

E: Sounds like you have a very deep-rooted connection to the natural world; what is your relationship to water specifically?

M: One of my earliest memories of water is going to my grandfather’s cottage on Lake Erie—moldy and damp, cluttered with outdated magazines, discarded fishing gear, remains of his cigars. The cottage wasn’t the focus, the lake was: murky water, sweetly scented, an endless horizon. We’d go a few times a summer, occasionally even sleeping over, “camping” my mother called it. I already knew how to swim.

I wasn’t sure about the lake thing. I often returned from those trips with a rash that I would finally diagnose 50 years later as cercarial dermatitis. But I was sure about water.

Floating. Frolicking. Holding my breath. Diving for treasure. Playing mermaid.

Going to the pool, or the lake meant capital P-L-A-Y.

Living on a Caribbean island introduced me to other forms of water play: snorkeling, body surfing, boogie boarding, and open water swimming. I also saw first-hand the destruction water unfurls through hurricanes.

After my father died, all I wanted was to swim: to go to that cocoon of soundlessness. I yearned for the embryonic hush of time before time.

Going into cold water offers a complete opposite sensation. The brightness of cold never fails to force me into the present moment. This embodiment practice teaches me presence, makes me feel powerful, and connected me with a community of people. Quotidian and ritual help me turn all of this into more than just practice, but also the works created for this exhibit.

E: Thank you for sharing that, what an incredible introduction to your work. So, how did all these experiences eventually lead you to connecting your ideas about the natural world to women?

M: After I did Water 23, the 95 days between the solstice and equinox of dipping, I went to a residency in Tennessee and two of the artists, Suzi and Brece were also at that residency. There were a few others in our group and the eight of us went daily around 4 pm to Little Pigeon River and dipped. The communal nature, the sharing of this challenging experience (the water was 37-41 degrees and the air temperature was similar. That’s really cold.) was a powerful one. I had been thinking about how I might “make art” in a different way, in a way that did not create “more stuff” in the world. I was looking at performance artists and walking artists and that led to creating Women Walking to Water–initially a series of conversations and gatherings centered on a walk, a dip, and a meal. The meal was HUGELY important. The word companion, if you look at it’s origins, it comes from Old French to literally mean “breaking bread together”. The gatherings were really the art!

E: Amazing. What is the significance of the location featured in most of the photography and artwork made for the show?

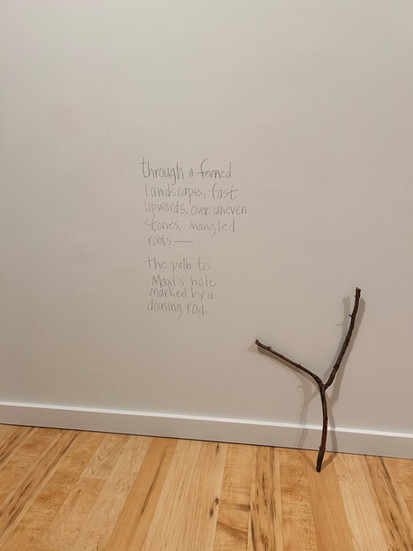

M: The location is Maxi’s Hole, the place we walked to and dipped monthly. It’s about ¾ a mile from my house. In 2023, I walked to this spot and dipped into it nearly daily for 95 days, from the summer solstice to the fall equinox. It’s a place my husband, my family, my friends, we go to her regularly to pray, to dip, to offer gratitude, to celebrate.

E: When did this idea come to you, how long did it take to create the work you made for this exhibition?

M: I asked the women in the monthly gathering if they wanted to create an exhibit in late September. We had a meeting in October, November, and December to discuss and plan. So not a very long time.

E: What inspired this to become a group show?

M: It became clear as the monthly gatherings went by that water and walking was showing up in our own individual practices. We wanted to see where that might lead to, and to also honor this sacred space that hosted our monthly gatherings.

E: Can you talk about the artwork featured on the exhibition pamphlets and flyers?

M: These are temperature charts from Maxi’s Hole, where we dipped from 2023 and 2024. The lower green and light brown are 2023, the other two colors are 2024. You can see that 2024 was much, much, much warmer.

E: What is a wilderness mindset?

M: Wilderness Mindset is a methodology and framework. To practice Wilderness Mindset, you deliberately place yourself into spaces that challenge and force acceptance of the unpredictability of the present moment. Wilderness Mindset provides a way to embrace uncertainty and practice embodiment through attention to place, sensory inquiry, movement, and a dance with the unknown and uncomfortable.

E: Every piece of your work is so authentically acquired and intentionally weaved together. So, tell me why was the song, People Get Ready, For The Cold to Come, chosen to open the exhibit through a group harmonizing exercise?

M: Well, I wrote the words to this song after Curtis Mayfield’s People Get Ready, a classic protest song as my structure. We decided to sing it as a way to create a sense of connection and community in the gallery space.